Confessing, obsessing and professing: Carly Simon bares her soul

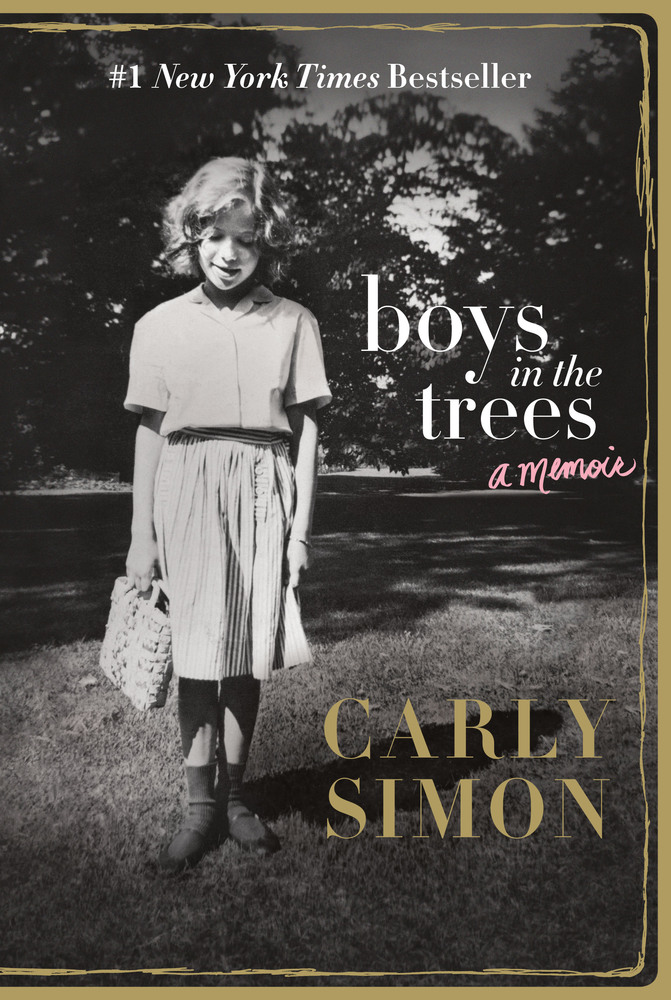

Boys in the Trees: A Memoir

By Carly Simon

Flatiron Books, 2015

Image source: us.macmillan.com/boysinthetrees/carlysimon.

Carly Simon's voice is a stand-in for some of our messiest feelings and most iconoclastic instincts. Unlike most “70's singer-songwriters” she is (lazily) compared to, she is actually extraordinary. Her slightly wobbly pitch, willingness to confess her vulnerabilities and insecurities, musical experimentation, and unabashed awkwardness are part of her charm. She is not easily categorized, and though her life has been tabloid fodder at times in her career, she remains not quite known.

After reading her lucid memoir Boys in the Trees I hope listeners and critics retire the clichéd notion of “singer-songwriter" as a genre. Simon, along with Joni Mitchell and ex-husband James Taylor, is one of the main icons of the term. Yet, during her most tumultuous time emotionally (circa 1981 when her marriage to Taylor was reaching its nadir) she turned (mostly) to the words and music of Hoagy Carmichael, Duke Ellington, Rodgers & Hart, and Stephen Sondheim to express her feelings on the standards album Torch. She recorded 1990’s My Romance, 1997’s Film Noir, and 2005’s Moonlight Serenade, all standards albums, under slightly less stressful circumstances, but my point is that she is as much a singer as she is a writer.

This upends the singer-songwriter designation in a number of ways. When we use this generic descriptor as a genre it presupposes original songwriting as the distinguishing characteristic of the performer. Yet, like Simon, Mitchell has done a lot of covering in her career including recording a 1979 album of Charles Mingus’s melodies and releasing multiple torch song sets in the 2000s. Taylor has scored many of his bigger commercial hits covering Motown, Stax, Brill Building pop and rock ‘n’ roll oldies. In the 2000s he’s recorded two cover albums, several Christmas albums and only released two albums of new songs. Paul Simon is also considered a 1970's “singer-songwriter” and comparatively speaking, he has released almost entirely original suites of songs throughout his career.

The notion of questioning music industry clichés is apt when assessing Carly Simon’s career. Unlike Mitchell, whose work has been saluted in jazz by Herbie Hancock, Ian Shaw and Tierney Sutton, her catalog has not yet generated album-length tributes. Her ex-husband, and occasional musical partner Taylor has released more platinum sellers (his greatest hits albums are big catalog sellers), he tours relentlessly thus regular expanding his audience, and like Mitchell, he is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. In essence, they have more critical respect than Carly Simon.

This is an interesting reality as Carly Simon has continually dashed expectations in many regards musically, and her eloquent approach to her memoir is no exception. To my ears Mitchell’s last significant album was 1976’s Hejira, and Taylor has never topped the quality and consistency of 1970’s Sweet Baby James. Simon has a more eclectic and adventurous career. Even when Simon was releasing a succession of prototypical “singer-songwriter” sets from 1971-80 she recorded a lot of material distinctly tailored to her voice and persona. In other words despite her professed desire in her memoir for her early albums to serve as demos for other singers (“…I just want to sit back and write songs and be the composer-at-arms,” 188), the singularity of some of her songs is what makes her special. Her best material often transcends easy interpretation. This might seem like an insult, but when you think of the countless bland and unrevealing renditions of “Both Sides Now” and “Fire and Rain” recorded in the 70s and beyond it puts her work into relief.

In the late ‘70s Simon also began revealing new colors: The dashing James Bond anthem “Nobody Does it Better” (she didn’t write it) is an unusually athletic and sensual performance I can’t imagine Joni Mitchell (or Carole King or Melissa Manchester, or Karla Bonoff, or Wendy Waldman) singing. The warm R&B flavors she delivers on “You Belong to Me” is surprising and winning. Torch is uneven but she sought out the treasures of pre-rock pop before most of her peers, and her rendition of Sondheim’s then new ballad “Not a Day Goes By” (from Merrily we Roll Along) is definitive.

Simon reasserted her relevance to popular music on this thoughtful 1987 album. Copyright © Arista Records.

Like a lot or pre-MTV singers she released her share of feckless trendy dance-pop before returning to her authentic sounds. In 1986 she released the beautiful movie theme “Coming Around Again” (from Heartburn) which was also the name of her “comeback” album. On this ballad heavy set she grew out of her adolescent fantasies and began authentically capturing the realities and anxieties of her generation about love and family as it reached middle age. Little of what her peers released at the time was even close sonically or thematically. Four hit singles and a platinum award later she released the brilliant Oscar winning film song “Let the River Run” (from Working Girl) which, as Jack Mauro’s liner notes of her 2002 Anthology noted, “It was written for Working Girl, and I can’t help but speculate on what the film’s theme might have drawn forth from other songwriters. At least several would have undoubtedly been career-issue specific” but “Carly Simon took her customary wide lens of viewing a scenario and got so far out she broke the zoom. She saw a story about a frustrated secretary’s struggle for recognition and saw aspirant who ever wanted something.”

Her 1990 album is a masterful meditation on growing up. Copyright © Arista Records.

1990’s Have You Seen Me Lately was more of an adult contemporary hit than a huge seller, but it built on Coming Around Again’s themes exploring aging and mortality even more gracefully. In the ensuing 25 years Simon has built a formidable discography comprised of standards albums and original pop songs, as well as interesting diversions. In addition to her attempt at opera (1994’s Romulus Hunt) and writing children’s books, she released a fantastic Brazilian inspired album 2007’s This Kind of Love, with songwriting contributions from Jimmy Webb, Wade Robson, and her children Ben Taylor and Sally Taylor. Though I would never think of Simon and samba together she sounds more vibrant and inspired than ever. Whereas Taylor trudges along with his steady but predictably mellow style, and Mitchell’s voice has become a withered, wizened character after decades of smoking, Simon’s rhythmic adaptions and harmonic flights feel both new and right for her.

Simon integrated Brazilian rhythms and textures on this unexpected delight from 2007. Copyright © Hear Music.

The Carly Simon common sense primer is as follows: Simon grew up the privileged daughter of a publishing maven. She questioned her bourgeoisie roots as part of a new vanguard of female singer-songwriters. She met James Taylor and they became one of pop’s premier celebrity couples before divorcing. She suffers from immense stage fright. She has had an up-and-down career—successful in the early ‘70s, declining in the mid ‘70s, picking up steam with a few hits in the late ‘70s, floundering in the early 80s and rebounding in the late 1980s, before becoming a “heritage” singer in the 1990s. This rough outline feels increasingly suspect when she tells the story.

Simon has long transcended the sensitive singer-songwriter-holding a guitar-mewling about lost love cliché. She is, more than anything, a highly expressive emotional confessor. And if she sometimes reveals too much, and does so a bit messily at times its part of her idiosyncratic charm. Though several of her songs are bonafide anthems, the kinds of songs people inevitably sing when they’re on the radio or blaring at a baseball game, she is not the commercial populist her longevity might suggest. I would argue that in terms of quirkiness, eccentricity, idiosyncrasies and other short hand terms we use for singular talents she’s been more of an acquired taste than many of her peers. These qualities are important to keep in mind as you read Boys.

Rather than writing a sprawling account of her entire life, reviewing the highs and lows of her musical career, or sharing platitudes, her memoir is a nuanced account of her emotional states during childhood, adolescence and early adulthood, and her first marriage which ended in 1983. She organizes it into three sections, and it’s fitting the sections are labelled as “Books” because they feel carefully and tightly crafted. The same vulnerability characterizing her best lyrics shines through; regardless of who is in what Hall of Fame, or who won what Grammy, her writing reminds you she has a deft lyrical touch and a remarkable prowess with language.

Book One: Carly is the insecure youngest daughter overshadowed by her sisters, seeking parental approval from her nouveau riche mother Andrea (“…Mommy must have often felt out of place….though her personality was bright, generous, animated, interested, tailor-made for the glamour and drumbeat wit that surrounded her. She often didn’t feel up to the conversation that tried to involve her,” 12) and her remote father Richard. She paints a complex, but affectionate portrait of a charmed life defined by living with an extended family of relatives and visitors in to her parents’ Greenwich Village home (where she lived until 6) and their summer home in Stamford, Connecticut. As she describes it, “Half of the residents of 133 West Eleventh Street were musical…” (8). Her uncles Peter and Dutch, and her parents’ circle of mostly white friends is erudite, musical, and a natural inspiration to Simon, “Over time I would collect different sounds in my head, ways of hearing notes—a fourth here, a dominant seventh there, though back then certainly nothing had a name!—and harmonizing would come almost as easily to me as singing melody” (9). She affectionately describes how her mother’s suggestion that she sing to manage her childhood stammer, which began with singing a melody for “Pass the butter” at the dinner table (26).

She courts their love desperately and receives only mild reciprocity. Regarding her father she notes, “My inability to get and keep Daddy’s attention, and the suspicion that of his four children I was the one he cared for least, was a problem I’d spend my life questioning and compensating for” (14). Beneath the surface lies a surfeit of dysfunctions, well beyond sibling rivalry. A family friend sexually abuses her from the age of 7-13. Her mother and father are increasingly distant from each other, and she eventually takes on a 19 year old lover Ronny, hired as a baby sitter for Carly’s brother Peter. Ronny disgusts Simon and her sisters, and her father is strangely silent and passive toward the ongoing affair. At some point she wants more from her father than just more attention from than her sisters. These emotional needs emerge as his health deteriorates and he is conned out of what would have been his fortune as the Simon in Simon & Schuster. Richards dies in 1960 after a series of heart attacks and mini-strokes. Carly’s relationship remains unresolved and informs her wrestling with “The Beast”: “…the feeling that I was never good enough, or loved enough…the Beast was my envious feelings about everything I worried about not being” (106).

Book Two: Carly enrolls at Sarah Lawrence in 1961, but is barely present as she is busy cultivating her first serious relationship with Nick Delbanco, and developing her musical chops including learning chords and absorbing influences like Odetta, Judy Collins, Nat King Cole, and Harry Belfonte. By 1963 she and her sister Lucy have a budding folk music career performing in New York and New England as “The Simon Sisters” and record their first LP in 1964.

In 1965 the Sisters get gigs in London and Carly takes up with a slick boyfriend Willie Donaldson. They leave eventually, break up the group, and after a period of odd jobs and indecision Simon begins her solo career. After a few false starts, notably a series of sexist encounters she experiences from male producers and musicians which disillusions her, she collaborates on a few songs, notably “That’s the Way I’ve Heard it Should Be,” with her friend Jake Brackman. Simon sends out a demo and is (barely) added to the Elektra Records roster. Eventually her first album emerges, she garners a hit, and her career takes off.

Book Three: As her star rises, with a second album and hit “Anticipation” under her belt, she is reacquainted with James Taylor who she first met (as “Jamie”) on the Vineyard as a teen. Enchanted by his music and haunting persona they meet after a concert and quickly become a couple. For the first time she feels paired with a fellow outsider whose tenderness and sensitivity complement her sensibility. On their first night together she notes, “It was the nicest contact I could ever know, could have ever asked for, or ever remember” (227). Early into their relationship she figured out their attraction as “…James and I were linked together as strongly as we were not just because of love, and music, but because we were both troubled people trying our best to pass as normal” (240).

In 1972 he wins the Grammy for Male Pop Vocal and she is recognized Best New Artist; they’re America’s first couple of pop music for a time. As they settle into marital bliss and build a household on Taylor’s eternally-in-progress Vineyard house, she begins to notice his mercurial moods and his publicly known substance abuse problems grow more apparent and toxic. Ever the professional, she soldiers on recording her most successful single (“You’re So Vain”) and album (No Secrets) in 1973, and has her first child Sally. Taylor’s career begins floundering around this time and he grows increasingly difficult and unreliable.

This is amplified when their son Ben, who suffers a host of medical problems, is born. Overwhelmed by Taylor’s erratic presence and struggles with drugs Simon feels like a single parent. When she discovers various episodes of infidelity the marriage is permanently thrown askew. Through all of this she remains stubbornly in love, despite her better judgment, even going to the lengths of bribing someone to get keys to his New York apartment and going there directly to confront his mistress. Simon clearly tolerates a lot of dysfunction, but is equally honest about her neediness, idealism, and vengefulness. This includes her ambiguous relationship to Mick Jagger, a big source of struggle for Taylor, and her affair with sound engineer Scott Litt when she recorded 1980’s Come Upstairs.

The marriage sours and Taylor, who comes across as passive aggressive and conflict averse, eventually meets actress Kathryn Walker who he marries. According to Stephen Davis’s biography of Simon, More Room in a Broken Heart, she was convinced that Walker rather than Taylor was responsible for the legal divorce (he’s perceived as too passive), and frustrated that she got the sober version of Taylor after over a decade of marriage (314). Simon’s tone in the book’s final chapter and epilogue is surprisingly rueful instead of bitter toward Taylor, though you feel she has earned the right to feel burned. She reflects that, “Looking back I made lots of mistakes. I remember and have made peace with each one, just as I forgive James for anything he may have done or not done” (370). I doubt he would formally respond to Simon’s characterizations. He seems to have moved on (he has remarried twice and had additional children); she is striving for clarity: “I am not the type of person to let go of my past easily. My memory is too good” (367).

Readers looking for insights into her music, especially the inspirations for songs and her process will find plenty of material. But her scope is vaster than hagiography. I recommend Sheila Weller’s intertwined biography of Simon, Carole King, and Joni Mitchell Girls Like Us (2008) or Davis’s biography for more musical coverage of her oeuvre.

Boys in the Trees is more of a tone poem than a typical biography. It’s highly readable because, like her finest music, she’s unafraid to let you in and the result is more like a lengthy conversation between friends, with exciting pit stops, diversions, and confessions than a rote recitation. Like the artist, the story Boys in the Tree tells and the voice it affects, is extraordinary.

COPYRIGHT © 2016 VINCENT L. STEPHENS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.