A Reckoning for the Queen of Soul

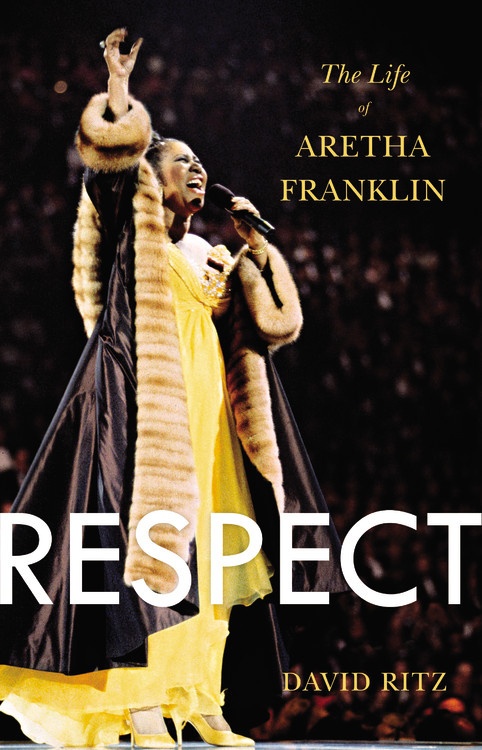

Respect: The Life of Aretha Franklin

By David Ritz

Little, Brown and Company, 2014

If “soul” is a decision to reveal rather than conceal Aretha Franklin, the Queen of Soul, has long deserved a thorough critical examination of her storied life and career. 1998’s facile autobiography From the Roots, written with biographer David Ritz, was definitely not it. As Ritz reveals in his 2014 Franklin biography Respect Franklin was very guarded about the depth of her story revealed in Roots and the result was a bland, willfully distorted depiction. As the primary writer Franklin spent more time describing food and outfits, and dismissing other singers, than she did discussing her most compelling asset—her musical talent.

Copyright © 2014 Little, Brown and Company

She strangely breezed through her mother’s unexpected departure at the age of six, her teenage pregnancies, her father the Reverend C.L. Franklin’s controversial behavior, Columbia Records’ failure to mold her into a pop/jazz chanteuse, or even the ongoing pressure for an aging singer to remain relevant in the youth-driven pop market. Rather than letting you into her hopes, fears, and aspirations during these important intimate touchstones she withheld them. The resulting tale was slight and strangely soulless.

A complex singer deserves a commensurate biography. Mark Bego’s Aretha Franklin: The Queen of Soul (originally published in 1989; revised in 2012) which primarily relies on secondary source materials, is an adequate chronological overview of her career including sales figures, awards, reviews and Franklin’s comments from interviews. Matt Dobkin wrote a briefer but more probing musical analysis of Franklin in his chronicle of the recording of her greatest album 1967’s I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You in a 2009 book of the same name. Dobkin sprinkled the book with insights on her career beyond this creative pinnacle but did not aspire to cover her entire life.

Ritz’s Respect goes further than any existing book in unpacking Franklin’s life and musical legacy. His unflinchingly honest portrait of Franklin—informed by Ritz’s interviews with her family, including her brother Cecil, sister Carolyn, and cousin and Franklin background singer Brenda Corbett, among others; her former booking agent Ruth Bowen; former record producers; and other singers (i.e. Ray Charles, Etta James, Carmen McRae)—is an honest, nuanced work that conveys multiple facets of her life. He presents her, warts and all, while still conveying fundamental respect for her artistic achievements. After reading the book I felt that Ritz’s introductory claim that “I have love and compassion for her as a sister and a believer. I stand in awe of her artistry” was credible.

Franklin publicly accused Ritz of writing a hatchet job. Based on his depiction of her as having controlling tendencies rooted in pride, vanity, and insecurity, this reaction is unsurprising. What Ritz does throughout Respect is walk readers through her life carefully exploring her family dynamics, chronicling her prodigious early musical gifts, and the ways these manifested in her first adult professional phase at Columbia Records.

Carmen McRae, Etta James, and producer Clyde Otis’s commentaries are particularly illuminating about her breakthrough moments and her struggle to gain an audience in the early ‘60s. From a musical perspective, it’s interesting how artists in other genres noticed and appreciated Franklin’s artistry, even though she was an unproven upstart. Franklin should be grateful for this critical attention to the oft-maligned Columbia years; Ritz is one of the few writers to acknowledge that this was not an entirely fallow period.

He also covers her time recording her first Atlantic album (I Never Loved a Man) at Muscle Shoals thoroughly, including the vivid impressions producer Jerry Wexler and the studio’s musicians had to her advanced piano playing and arranging. Franklin’s ex-husband Ted White infamously clashed with some of the musicians and his tumultuous marriage to Franklin is addressed by a range of witnesses.

By the early ‘70s Franklin was the most consistently popular female singer of the late ‘60s-early 70s and a multi-Grammy award winning superstar. Despite her success her insecurities about her weight, and anxieties about other singers stealing her thunder, including her sisters and newer singers like Natalie Cole, started to creep into her public persona. This began a cycle of her periodic announcements about new business ventures and film roles that never came to fruition, fluff stories about Franklin’s diet and exercise regime,, and countless stories about unidentified men she was courting. Each pointed toward an apparently pressing need to remain relevant. By the mid-70s her albums and singles were slipping in quality and sales. The story of her scooping Curtis Mayfield’s Sparkle soundtrack from her sister Carolyn is especially harrowing. After that 1976 triumph her Atlantic Records period lapsed into obscurity.

Though these unscrupulous behaviors populate the book Ritz notes many episodes of generosity ranging from a series of donations to civil rights causes to Franklin giving her 1972 Grammy to the great R&B singer Esther Phillips as a gesture of acknowledgment. I suspect there’s enough gossip about Franklin from Ritz’s vast range of sources that he could have easily reduced Franklin to an emotionally challenged shrew. But tonally Respect is characterized by an ongoing passion for Franklin to triumph. As he states in the introduction he admires and respects Franklin deeply.

This sincerity remains especially important as he describes her declining career in the mid-to-late ‘70s and her rebound with trendier material at Arista Records in the early ‘80s. Ritz’s sources consistently note how Franklin’s resentment of other female singers intensified as a generation of new mega pop divas (i.e. Madonna, Whitney Houston) emerged. She was often less than gracious competing with them rather than appreciating their good fortune.

Her desire to stay on top also leads her to fall under the commercial spell of record mogul and producer Clive Davis. He helped keep her current to a point but mostly steered her away from her gospel, blues and jazz roots toward pop ephemera. Though there is limited evidence of Davis acting as a Svengali in Franklin’s career the stylistic grab bag her Arista albums certainly evokes the kind of crass commercialism he trumpeted in his autobiography The Soundtrack of My Life.

As long as the industry showered her with awards (she won five Grammies from 1982-89) and reiterated her Queenly status the less able she was to view her own talents with clarity. Important personal issues shaping her life during the ‘80s included her struggle to find suitable relationship, her grief supporting her comatose father who was shot during a burglary and struggled through illness for years, and her anxieties about travel, which led to legal and financial issues.

If anything what emerges from Respect is the inability of talent itself to shield artists from the emotional minefields of life—relationships, family, career setbacks, etc. as well as its ability to sustain someone emotionally. Franklin appears as a dark, troubled, almost unknowable soul who channels her energies into her music. There is clearly immense pressure on her to be “Aretha Franklin”—a daunting task when one considers how difficult it would be for anyone to approximate the impact of “Respect,” “Chain of Fools,” “Ain’t No Way,” “Natural Woman”—seminal recordings made almost 40 years ago. Similarly, Franklin’s LPs were popular but never sold at the epic multi-million levels Madonna, Houston, Janet Jackson, Mariah Carey, and Celine Dion once sold at their commercial heights.

Artistically, it’s hard not to agree with Wexler and Ritz’s point of view that Franklin could extend her stature by returning to the jazz standards she tackled at the beginning of her career. With her wealth of life experience and professional seasoning American Songbook standards seem like more suitable vehicles for her than the pop confections currently populating mainstream radio. Giving up pop crossover efforts might restore her artistic mettle. Despite the late career triumph of “A Rose is Still a Rose” and special moments like her surprising performance of “Nessun Dorma” at the 1998 Grammies and her dynamic 1998 VH1 Divas performance her best work seems long behind her. But this does not have to be the case.

In 2014 she released Aretha Franklin Sings the Great Diva Classics, a cover album of songs popularized other female singers including nods to Etta James (“At Last”), The Supremes (“You Keep Me Hangin’ On”), and Adele (“Rolling in the Deep”). Though some critics reviewed it favorably and it sold moderately well no one sees her versions as definitive and it is all rather perfunctory. Surely she he has more to offer us than a jazzy rehash of “Nothing Compares 2 U.”

From Ritz’s account I sense that Franklin lacks clear artistic direction and suffers from an acute restlessness. Perhaps she needs an artistic mentor she can trust. Someone who can help her make smarter choices, but who is willing to be honest with her about the best ways to employ her voice (its diminished in range and power) and help her realize she does not need to compete with Katy Perry or Beyoncé.

If anything she might borrow a page from Natalie Cole a stylistic protégé of Franklin who has always given her respect even when Franklin was dismissive of her talents. Cole morphed from a slick pop-soul singer to a respected jazz-oriented interpreter in the early 1990s. Similarly, Franklin’s peer Barbra Streisand has recorded several artistically accomplished, commercially successful albums (2003’s The Movie Album, 2009’s Love is the Answer, and 2011’s What Matter Most) featuring adult material suited to her talents that bucks trends. Though Tony Bennett’s series of Duets albums may have run their course they paired him with (mostly) suitable partners (including Franklin) and found him a sizable audience.

Franklin deserves the respect she famously sang about, and Ritz provides it. He appreciates her art and makes the unusual choice to end the book with a deeply felt personal wish list to Franklin. Respect articulates complexity of her life and its haunting role in her music; it also offers a moral imperative for her to be fully present and authentic in both.

COPYRIGHT © 2015 VINCENT L. STEPHENS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.