Aretha’s Rainbow: Notes on Aretha Franklin’s music beyond ‘soul’

The loss of a musical and cultural titan as mighty as Aretha Franklin (March 25, 1942-August 18, 2018) naturally inspires critics, writers, bloggers, journalists and fans the opportunity to reflect on her legacy. I have listened to a wide range of Ms. Franklin’s music deeply over time and this month I discuss her remarkably underrated musical range and adaptability.

The cover of Aretha Franklin's 1961 debut album on Columbia.

We have commonly known Aretha Franklin as “the Queen of Soul,” a recognition of her talents as the most influential singer in Rhythm & Blues (R&B). But her ascent to this role was not inevitable. She has always had the talent and drive to move in any musical direction of her choice. Franklin grew up the daughter of Reverend C.L. Franklin a prominent minister and civil rights activist. As a “PK” (Preacher’s Kid) Aretha’s exposure to gospel music was the outgrowth of being raised in a church environment, especially during a time when the church played an even more prominent role as a social and spiritual force in the lives of African-Americans. Her father regularly interacted with luminaries in the gospel world such as singer Clara Ward, who nurtured Aretha, so her emergence as a young gospel recording artist at the age of 14 is understandable.

In the 1950’s gospel music was far more segregated from secular music than it is today. Most popular black singers of Aretha’s youth, including jazz vocalists such as Sarah Vaughan and Dinah Washington, and R&B singers who preceded Franklin, such as Ray Charles and Etta James, began their musical training in a church environment. Many singers, such as Roy Hamilton, Sam Cooke, and Washington achieved commercial success on the gospel circuit, before deciding to make the leap to secular music and “cross over.” Crossing over was such a major issue that many of gospel’s most accomplished voices, including Mahalia Jackson, Marion Williams and Shirley Caesar, always made it a point to note that they had opportunities to sing secular music but refused.

Franklin's first top 40 pop hit was "Rock-A-Bye Your Baby With a Dixie Melody" a pop song Al Jolson popularized in 1918.

Franklin’s ambitions, however, went beyond the circuit. Signed by John Hammond to sing at Columbia Records, her stint from 1961-66 is represents her complicated musical identity. While gospel vocal techniques, including the selective use of bent notes, melisma and call-and-response type arrangements, deeply inform Franklin’s singing, her taste in material extends well beyond the secularized gospel material known as R&B songs to include blues and pre-rock pop music from Broadway and film. Though she conveys a vocal intensity and emotional vulnerability best understood as “soul” her Columbia recordings tell a fuller story of her musical interests.

Her 1961 Columbia debut album Aretha (in Person with the Ray Bryant Combo) featured original songs such as “Won’t Be Long” with a strong flavor recognizable to R&B fans, but she also interpreted “Over the Rainbow” (from The Wizard of Oz) and “Ain’t Necessarily So” (from Porgy & Bess). These interpretations are distinctly Aretha-fied but cannot simply be understood as “soul” or “R&B. Like many musicians of her generation she absorbed a wide range of influences and these are as essential to understanding her career as hits like “Respect” and “Think.”

Yeah!!! released in 1965 is Franklin's finest jazz set at Columbia.

Columbia paired Franklin with many different arrangers and producers in search of commercial hits and this proved difficult. Franklin’s taste in material included a penchant for creatively reimagining tried and true standards (“Love for Sale”) and more contemporary (“If I Had a Hammer”) songs sung in jazz settings such as the superb jazz set Yeah!!! which could have made her the outstanding jazz vocalist of her generation. But she also enjoyed singing dated “showbiz” songs including “Rock-A-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody” made famous by Al Jolson in 1918 (!), and a flashy version of the pop warhorse “Won’t You Come Home Bill Bailey.” These kinds of songs, combined with period era touches such as strings and background choirs, found her at odds with changes occurring in popular music in the mid-1960s. This includes the transition of rock ‘n’ roll from dance-oriented music to more serious and sophisticated “rock,” the growth of R&B into “soul,” and newer variants in jazz such as “soul jazz” and the avant-garde.

Aretha's 1967 Atlantic Records debut focused more on Franklin's gospel roots and writing, playing and arranging skills than any of her previous albums.

Stuck in a commercial rut, she had not found consistent success in the pop, jazz and cabaret vein of Columbia and overtly sought a label that could help her secure hits on the radio and the record charts. At Columbia Records, she had 12 top 100 singles, with only one, the rather unfortunate “Rock-A-Bye,” hitting the pop top 40. Considering the social and racial segregation of the 1960’s she was more popular on the “black” singles charts where she had 8 top 40 songs though few were major hits. Atlantic Records, under the guidance of producer Jerry Wexler, helped Franklin realize her ambitions by providing more leeway to select songs, paly piano and arrange her material. From 1967’s “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” onward she grew into a creative and commercial acme that went until about 1974. Had her career been assessed by the first singles she released from 1967-68, which includes (in order): “I Never Loved a Man,” “Respect,” “Baby I Love You,” “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman,” “Chain of Fools,” “(Sweet Sweet Baby)Since You’ve Been Gone,” “Ain’t No Way,” “Think,” she would have had the greatest streak of winners of any singer of her time. What’s so amazing is that she continued to produce more classics, on an almost routine casual basis, including her versions of “I Say a Little Prayer,” (1968) and “Bridge Over Troubled Water” (1971) and original compositions such as like “Call Me” (1970) and “Daydreaming” (1972).

Though the late 1960’s-early 1970’s is Franklin’s prime “classic” period this does not mean everything she recorded was classic. Franklin became an artist before albums were assembled as meticulously as they eventually became in the late 1960’s era of rock “concept” albums. Essentially her albums were compilations of potential singles and whatever was recorded recently. This shifted with 1969’s more conceptual big band jazz set Soul ’69 and on the gospel extravaganza 1972’s Amazing Grace. I mention this because even as her albums became more uneven in the early 1970’s there was still at least a handful of classic individual performances which is more than could be said for most artists. No matter how uneven an album, such as 1974’s Let Me in your Life, might be there was a classic performance like “Until you Come Back to Me (That’s What I’m Gonna Do)” that reminded you why she stirred so much excitement in 1967. Except for 1976’s Sparkle soundtrack the mid-to-late 1970’s was a commercial nadir as Franklin searched for suitable material to apply her naturally potent voice, a search complicated by the expanding strands of black pop which included quiet storm, funk, disco and Philly Soul.

1985's Who's Zoomin' Who? was a mid-career triumph hghlighted by "Freeway of Love."

Searching once again for “hits” Franklin took a cue from Dionne Warwick’s success at Arista Records and signed with the label. Many critics have noted how this era pales with her classic period. I respond to this in two ways. First, any artist’s peak would pale in comparison with Franklin’s late 1960s-early 1970’s hot streak. At Atlantic she as able to synthesize nearly all her disparate influences and interests into a cohesive style that was rooted in gospel but drew from a panoply of American music strands. Second, like most major artists Franklin faced a generation gap and major industrial and technological changes in the music industry. Franklin was 25 when “Respect” became a hit and nearly 40 when she had her first Arista “hit,” the ballad “United Together.” Franklin was not going to revert to the jazz and pop she began with as much of this material had been interpreted continually by a wide variety of singers since the 1910’s and she was interested in authoring new hits. Further, she was entering into an industry more defined by electric production technologies (e.g. synthesizers), personalized audio delivery systems (e.g. Walkman’s) and promotional outlets such as MTV, as well as a narrowing of radio programming menus.

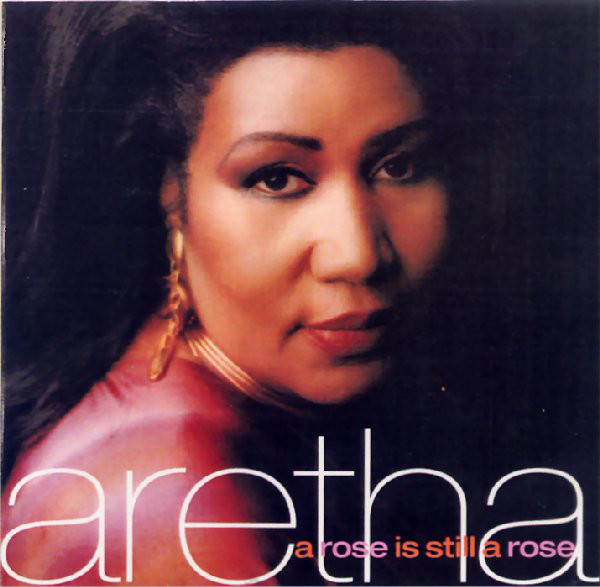

In this more codified and demographically focused market Franklin made a noble effort to employ her still rich voice and sharp pop instincts to remain a vital pop figure. For someone of my vintage (ahem, mid-1970’s) I knew songs like “Respect” and “A Natural Woman,” as they were too iconic (and played on oldie stations) to not know, much like “Unchained Melody” or “Reach Out I’ll Be There.” I also experienced Franklin’s performances of 1982’s “Jump to It,” 1983’s “Get it Right” and the monstrous 1985 radio and MTV hit “Freeway of Love.” As a young listener, I was both aware of Franklin as a revered singer with a rich past and as a contemporary artist whose hits such as “Freeway,” “Sisters Are Doing It Themselves” and “I Knew You Were Waiting (For Me)” were as good as pop got in the mid-1980’s. This was new music and it was commercially viable and genuinely exciting. Sustaining the commercial success of these hits eventually became harder as Franklin’s fusion of gospel technique and sleek modern production styles competed with hip-hop, New Jack swing, modern rock, and other emerging styles. The quality of material she recorded for Arista from the late 1970’s through the early 2000’s finds her locating ways to adapt her sound to the times. Sometimes this resulted in a sublime fusion, such as 1994’s “Honey” and 1998’s “A Rose is Still a Rose,” and sometimes it resulted in her “oversouling” on slight material or straining too hard to sound “hip.”

1998's A Rose is Still a Rose was one of the most popular and well-received albums Franklin released in the last 20 years of her career.

Franklin’s efforts to remain current has inspired controversy among many musicians and critics. For example, several of her past producers such as Wexler and arranger Clyde Otis, wanted her to skip the contemporary pop music scene and focus on being a jazz-oriented singer. Yet Franklin has never felt like a singer seeking to be confined to one style. She took risks “crossing over” from gospel to secular music and transitioning from the jazzy pop style of the 1960’s to the more overt “soul” approach of the late 1960’s. Most musical artists are lucky to excel in one style and she found a credible voice in multiple styles and eras. As such, her missteps must be considered in the context of their creation and the transitory nature of pop music.

While many of her peers may have been associated with a defined time in the past and lauded for their endurance, she strived to achieve ongoing relevance. A talent like hers transcends charts, sales and awards. Her spectacular performances at the 1997 VH1 Divas Live concert, at the 1998 Grammys singing “Nessun Dorma” and stopping the show with “A Natural Woman” performance at the 2015 Kennedy Center Honors, attest to a highly cultivated musicality and showmanship. Though many singers think “soul” is only about raw emotion Franklin has deep roots that helped her balance the emotional and technical needs of her material. Her versatility, improvisational skill, musical technique and sheer heart are uniquely her own.

************************************************************************************************************

Please enjoy these two playlists I compiled via Spotify:

1961-74:

https://open.spotify.com/user/vls008/playlist/6JtD03J7GmCk6I3RzUGHpy?si=HcT4MnSWSCm7GoYwBgbLFw

1980-2003:

https://open.spotify.com/user/vls008/playlist/6JtD03J7GmCk6I3RzUGHpy?si=HpPb9AFXTqOOhD0PcXqFwg

COPYRIGHT © 2018 VINCENT L. STEPHENS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.