Learning to Listen excerpt 12: From the shadows: Natalie Cole finds her soul

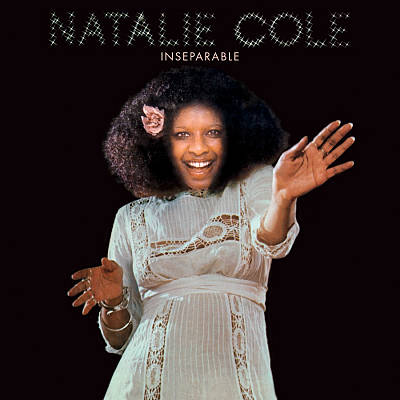

Riffs, Beats, & Codas celebrates the life of the accomplished singer Natalie Cole who sadly passed away on December 31, 2015 from congestive heart failure. Cole established herself as a fresh new voice in popular music in 1975. Her debut album Inseparable earned her two Grammy Awards as Best New Artist and Female R&B Vocal Performance. She repeated a win in this category in 1976, and received two consecutive American Music Awards in 1977 and 1978 as Favorite Female Vocalist Soul/R&B. Cole remained a pop and R&B staple commercially through the late ‘70s-early ‘80s while navigating drug addiction. After a commercial downturn and time spent in rehabilitation she came back commercially in the late 1980s with hits like “Pink Cadillac,” “I Live for Your Love,” and “Miss You Like Crazy.” She redefined herself as a jazz-oriented interpreter on three Grammy winning sets 1991’s Unforgettable with Love, 1993’s Take a Look, and 1996’s Stardust. She continued exploring various songs in the pop, R&B, and jazz repertoire throughout the late 1990s and 2000s including 2002’s Ask a Woman Who Knows, 2006’s eclectic Leavin’ 2008’s Still Unforgettable, which won the 2008 Grammy for Best Traditional Pop Vocal Performance, and her final album 2013's Natalie Cole en Espanol. In addition to her recording career Cole was an active concert performer, acted in numerous television series, and appeared as herself in reality programs and performing music specials. Please enjoy this essay on Cole's unique legacy excerpted from my essay collection Learning to Listen: Reflections on 58 great singers.

Source: www.allmusic.com.

Natalie Cole (b. 1950) grew up in the shadows of two of popular music’s towering figures. Over time she has emerged as a distinctive vocal artist with a unique flair. Cole is of course the daughter of innovative pianist/bandleader and suave vocalist Nat “King” Cole who pioneered the jazz trio (piano-guitar-drum) format in the ‘40s, which became a staple of jazz, and transitioned into a stellar solo career. At Capitol he was a prolific recording artist whose LPs with arrangers like Gordon Jenkins, Billy May and Nelson Riddle parallel Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra’s innovative explorations of the album format during the 1950s.

In addition to his influence as a musician and popularity as a vocalist he was one of the first African-Americans to have a weekly television variety show, The Nat King Cole Show. Though the show ended because of objections by Southern television stations that he was too “controversial” (largely because he shared the stage with white singers) his musical and cultural prominence culminated in Cole’s immense iconicity as a representative of black cultural achievement. Musically gifted, eminently likable, and the embodiment of class and integrity, he was an icon whose death in 1965 from lung cancer devastated a public who embraced him as an icon.

During her childhood Natalie was exposed to the music of her father and his peers, and developed her own musical talents. As she shares in the liner notes of 1991’s Unforgettable with Love she met many of popular music’s elite, including figures like Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald whom she referred to as “uncle” and “aunt” respectively. In the liner notes there are also photos of her fronting a band of other teenage children from prominent California musicians’ families. She also occasionally made appearances as a singer with her father. Rather than presuming music was “in her blood” because of her lineage (her mother Maria sang with the Duke Ellington Orchestra and uncle Freddy Cole is a jazz pianist and vocalist) it is more accurate to note that she cultivated her musical talents at an early age. As Cole experienced her adolescence she witnessed the ascent of musicians of her generation reconfigure popular music’s past into styles reflecting their own musical influences and social perspectives. Rock and soul music were central to this, and soul’s most prominent figure during the late ‘60s was Aretha Franklin.

Beginning as a blues and jazz flavored stylist Franklin had an uneven career at Columbia Records—which struggled to find the right settings for her talents—before recording for Atlantic Records from 1967-79. There she asserted a creative input into her recordings as an arranger and pianist (Franklin has noted her frustration at not being credited as a producer) injecting pop and R&B songs with a fusion of gospel singer’s sense of emotionalism, a jazz singer’s sense of swing, and the interpretive perspective of the blues. She further propelled R&B into the mainstream building on the innovations of Ray Charles and Sam Cooke. Essentially she “gospelized” the secular song with a unique synthesis of influences, infused with a distinctly feminine outlook on sexuality and romance. There were many gifted female R&B singers who preceded Franklin including such notables as Ruth Brown, LaVern Baker, Etta James, Tina Turner, and Irma Thomas. But Franklin achieved an unheralded level of consistency in a genre often more notable for singles than great albums. She also achieved a stylistic balance; she could testify on “I Never Loved a Man,” coolly saunter through “Respect,” and tap into a vulnerable sensuality on “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman.” Even these landmarks only hinted at the versatility and adaptability she evinced in her prime.

After college Cole chose to become a recording artist and her 1975 debut effort Inseparable was critically well received and commercially embraced. Many noticed the clear influence of Franklin on Cole’s singing. Like Franklin she sang with a buoyant gospel inspired spirit and was also a credible ballad and torch song singer. The key recording linking Franklin to Cole is her 1968 rendition of Sam Cooke’s “You Send Me” particularly toward the end of the song where Franklin ends by double tracking her voice and harmonizing, singing several bursts of the refrain “You send me” “You thrill me” “You kill me” “Yeah yeah yeah yeah” like improvised vocal horn flourishes. On Cole’s similarly upbeat hit “This Will Be” a big part of its allure is the staccato, double-tracked chorus “This will be” (pause) “You and me” (pause) “Eternally” and then the rapid fire succession of phrases “So long as I’m living/True live I’ll be giving…”

Cole duplicated this double tracked single-voiced choral approach on subsequent singles like “Mr. Melody” and “Sophisticated Lady.” The Franklin influence on Cole is significant in the context of ‘70s R&B since the late 1960s/early 1970s was a very transitional period in R&B and black pop, reflecting broad changes in the industry. Singers were increasingly focusing more on albums than singles which afforded more room to sing longer and more elaborately arranged songs. Among black artists this shift also coincided with music more focused on mood and languor than funk. Roberta Flack’s First Take (originally released in 1969 but commercially unsuccessful until 1972) and its lead single “The First Time ever I Saw Your Face,” Isaac Hayes’s success with Hot Buttered Soul, Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, Donny Hathaway’s Extension of a Man, and Smokey Robinson’s Quiet Storm are key hallmarks of this progression in black music toward an almost symphonic conception of albums as coherent suites with a sustained mood rather than collections of singles.

What distinguished Cole is that she was a “modern” ‘70s artist whose image was that of a sophisticated stylist in the vein of Diana Ross, but musically she maintained the funky gospel aspect of ‘60s R&B. In a sense she updated the soul sound for a new decade recording albums replete with electric keyboards and strings, and featuring seemingly conventional romantic ballads that built to gospel style climaxes such as “I’ve Got Love on My Mind” and “Our Love.” A peculiar feature of her mid-70s LPs are touches of jazz including the brief scat interlude on “Mr. Melody” and her interpretation of “Good Morning Heartache” both on Natalie (1976); the swinging original composition “Lovers” on Thankful (1977); and the scat-laden interpretation of “Stairway to the Stars” on Don’t Look Back (1980). Though “jazzy” elements are common on many recordings by black female singers of the ‘70s, including stylists like Randy Crawford and Phyllis Hyman (discussed in the “Lost in the Mix” section), the consistent presence of these on Cole’s initial recordings hinted at a conversancy with swing jazz she eventually realized. As one might expect Cole was very protective of her father’s music and was understandably reserved and anxious about recording material that might invoke comparisons.

The promising fusion of ‘60s R&B, ‘70s quiet storm soul, and light jazz she initially presented in 1975 became increasingly compromised as Cole succumbed to drug addiction; her late ‘70s-mid-80s recording output (1979-1985) is notoriously inconsistent and these recordings made it easy to write her off as another fading rock music casualty of hard living. Then in 1987 after a stint at rehab she returned with a new vigor on Everlasting, recording material that was memorable enough to reinvigorate her career as a contemporary interpreter of pop, R&B and adult contemporary material, a pattern that continued on 1989 ‘s Good to Be Back. Both albums established the singer’s commercial acumen and that her voice was still in fine shape. Listening to these albums her personality is more muted, the material is predictable and conservative, and in light of the success of emergent voices in R&B like Anita Baker, her ability to innovate seems in the distant past.

Interestingly, instead of mining the same adult contemporary sound she confronted her fears of recording her father’s music on 1991’s Unforgettable with Love. Cole was rightfully lauded for her sophisticated uptown soul sound in the mid-1970s, but for some observers the Franklin influence sometimes overshadowed her individuality. Further, the declining quality of her music in the 1980s inhibited the typical maturation into a distinct personality vocalists usually experience. Beyond restoring her commercial standing the ’87 and ’89 albums never quite revealed new colors on her palette beyond professionalism and adaptability. In an unexpected move Cole nurtured the jazz leanings she had into a full-length album of standards associated with her father spanning from his Trio days to his solo career of the early 1960s.

Though Linda Ronstadt had commercial successes with her trilogy of standards albums from 1983-86, Barbra Streisand topped the album chart with The Broadway Album, and Harry Connick Jr. was one of the few jazz-influenced vocalists to gain commercial acceptance, a standards album by an R&B singer was hardly a commercial proposition in 1991. Though a number of “retronuevo” R&B crooners and balladeers achieved commercial success in the late 80s/early 90s, the commercial rise of New Jack swing and hip-hop soul were rapidly changing the sound of black pop. A standards album could have easily seemed anachronistic and reactionary.

Despite the climate Elektra Records “greenlit” the album; this term is more frequently invoked in filmmaking but the metaphor makes sense for the album’s scale. For one thing the narrative—daughter of legendary musical icon interprets his music for modern audiences is Hollywood fare. And the album’s “hook”—her duetting with her father on the 1961 re- recording of 1953’s “Unforgettable”—is irresistibly sentimental. Elektra also contributed to the spectacular aura employing expensive “adult pop” arrangers (Marty Paich) and producers (David Foster and Cole’s then husband Andre Fischer), financing musicians in orchestral, big band and trio formats, employing background singers, and developing a marketing strategy that would appeal to contemporary consumers increasingly opening their wallets to hip-hop, modern rock, and other emergent pop variations.

Source: www.allposters.com.

Cole was the core of this spectacle and if she faltered the album could have become either the musical equivalent of the Edsel, an ugly heavily hyped disaster, or a career novelty whose mediocrity ensured her confinement to rigid soft rock and R&B commercial formulas. Instead Cole delivered a well realized set of interpretations that reflected her father’s influence but also showcased her own spirit. Unlike many of her pop predecessors who had recorded “rock torch” sets Cole was both technically equipped and emotionally adept at interpreting pre-rock songs in lush orchestral settings and in the more demanding, emotionally naked settings of a big band and small group.

Cole’s interpretive poise is remarkable in part because she sounds like a pro rather than a tourist. Though she sticks to the melodies and there is only minimal improvisation, she swings effortlessly and interprets lyrics with nuance which instantly aligns her with competent interpretive singers. Pop/rock singers are accustomed to recording over pre-recorded rhythm sections and singing in front of bands rather than as a voice in bands. Thus rock critics tend to cut them some slack in interpreting pre-rock pop. But Cole needs no excuses; in addition to singing with technical and emotional command, she and her arrangers take modern liberties like excising the goofy choir from “Orange Colored Sky,” creating a lovely medley of “For Sentimental Reasons/Tenderly/Autumn Leaves” and having the taste and restraint to avoid recording once popular Nat “King” Cole ephemera like “These Lazy-Crazy-Hazy Days of Summer.” By choosing a diverse array of tempos and arrangements Cole exposes her father’s (and her own) stylistic range and her ability to comfortably inhabit a variety of lyrical settings.

Unforgettable grew into a cultural phenomenon topping the album charts and winning Cole Grammys for Album, Record and Traditional Pop Vocal Performance, as well as awards for arranging, composing, engineering, and producing for others in the album’s cast of characters. The easiest way for Cole to follow-up on Unforgettable would have been recording another album of familiar pop standards. Or she could have built on its momentum and returned to radio-friendly adult contemporary pop-soul. Instead Cole chose to move beyond her homage to her father to salute other singers who impacted her career on 1993’s Take a Look and also revealed deeper jazz roots than Unforgettable suggested.

There are solid nods to obvious jazz goddesses including Billie Holiday (“Crazy He Calls Me,” “Don’t Explain”) and Ella Fitzgerald (“Swingin’ Shepherd Blues,” “Undecided”). But the most interesting reveals include her apparent passion for vocalese, on one woman multi-tracked versions of Lambert, Hendricks and Ross’s “It’s a Sand Man,” “Fiesta in Blue,” a reprise of her own composition “Lovers” and a gem from 1958 “All About Love.” Though a little bit of vocalese can go a long way she wisely sequences them to balance out torchy ballads. Gloria Lynne’s signature “I Wish You Love” and Carmen McRae’s rendition of “This Will Make You Laugh” inspire some of her more ironic, bittersweet ballad performances. She also initiates a trend that she continues to explore in excavating Nat “King” Cole obscurities. A hardcore Cole fan knows “Let There Be Love” from his lovely 1962 collaboration with jazz pianist George Shearing. The goofy “Calypso Blues,” which mocks “Yankee” ways (i.e. hot dogs, blond dye jobs) in mock Trinidadian patois is a Cole novelty from 1950 that she milks pretty expertly in its laidback island setting. Larry Bunker’s vibes and marimba really paint a lovely picture. Elsewhere Cole swings effortlessly, including “I’m Beginning to See the Light” and “Too Close for Comfort,” and is entirely comfortable working in a jazz setting with vets like Herbie Hancock (piano) and John Clayton (bass). Some critics viewed Take a Look as a commercial letdown compared to Unforgettable, but the comparison is nonsense. From a purely commercial perspective she could have sold a lot more albums if she had chosen garden-variety standards and packaged the album as orchestral nostalgic bliss. Instead she chose to record songs she clearly loves, many of which are obscure, in more jazz-oriented settings. Not the most commercial move circa 1993. That it hit the top 30 and sold half a million copies (and won her a Grammy for Jazz Vocal Performance) is fairly miraculous given the usual gap between pop and jazz. Take a Look revealed a new phase for Cole that went beyond formula.

1996’s Stardust probably appears to be a direct descendant of Unforgettable; she sings with Nat on a reprise of “When I Fall in Love,” there’s more orchestral material, and more producers than on Take a Look. The songs are also generally more recognizable for pop ears (i.e. “Stardust,” “What a Difference a Day Made”). But Cole continues to surprise you. The underperformed “To Whom it May Concern,” “Where Can I Go Without You” and “This Morning it Was Summer” are more nods to her father’s vast repertoire. Jazz heads will delight in her take on the lyricized version of Ahmad Jamal’s “Ahmad’s Blue” and bop composer Tadd Dameron’s “If You Could See Me Now” (first performed by Sarah Vaughan). She and Janis Siegel perform a tight, perfectly harmonized interpretation of Lambert, Hendricks and Ross’s spritely “Two for the Blues.” There is enough of a balance here between lush traditional pop, jazz material, and family heirlooms to legitimate Cole as a vocal artist with a genuine balance between pop accessibility and jazz chops.

In the course of five years Cole blossomed from a reliable pop singer with soul to an excellent interpreter of pre-rock pop and jazz. Snowfall on the Sahara is her first run at a genre-less album that showcases lessons learned in the pop, jazz, and R&B spheres. Cole dabbles successfully in a spectrum of popular styles. There’s the sleek adult pop on the title tune (co-written by Cole), classic R&B ballads (i.e. DJ Rogers’s “Say You Love Me,” Jerry Ragovoy’s “Stay With Me” and the Roberta Flack signature “Reverend Lee”), more L, H, & R jazz (“Every Day I Have the Blues”), lush balladry, most notably Judy Collins’ “Since You Asked,” and traditional ballads ranging from Patti Page’s “With My Eyes Wide Open, I’m Dreaming” to Leon Russell’s “Song for You.” Most surprising among this grab bag is her delightfully coy rendition of Taj Mahal’s “Corrinna” and a rollicking version of Dylan’s “Gotta Serve Somebody.” Just when she seems to have taken a permanent turn Cole expands her vision to include a seamless juxtaposition of material across era and genre.

Three years passed between Snowfall and her luscious standards set Ask a Woman Who Knows. Though several of the songs are associated with other pop divas, such as the title track (a Dinah Washington obscurity) and “My Baby Just Cares for Me” (Nina Simone), Cole approaches these tunes with little in the way of overt homage or concept. It’s just a lovely, luscious album. She swoons on a lush “You’re Mine You”; “Tell Me All About It” has a gentle Brazilian lilt that makes it sound like the best song Jobim never wrote (Michael Franks wrote it); and on Bob Telson’s “Calling You” she illuminates the song’s haunted contours, proof that her gifts are not confined to pre-rock standards. She and Diana Krall have fun on “Better Than Anything” with its litany of guilty pleasures, and she excels in the company of some of jazz’s most esteemed players, a benefit of recording for Verve.

Cole closed out the decade with the soulful Leavin’ and the swing set Still Unforgettable. Whereas Snowfall was a panorama of Cole’s eclectic interests she approaches the pop/rock/R&B songs of Sting, Des’ree, Kate Bush and Aretha Franklin on Leavin’ with more focus adding thundering drums, emphatic vocal arrangements and R&B grit. She transforms Fiona Apple’s “Criminal” from sultry rock to a popping R&B strut. “Love Letter,” best known to Bonnie Raitt’s fans as a mid-tempo slow burning tune, is a revved up, high octane number with more prominent percussion and gospel style background vocals. Elsewhere she bathes “Lovin’ Arms” in layers of dewy, sizzling regret. The best performance is an original soft-soul ballad “5 Minutes Away” with a hopeful lyric about finding love and gentle harmonies. The closet rock-folk interpreter in Cole also comes out on her version of Neil Young’s “Old Man” and Shelby Lynne’s “Leavin.’”

2008’s Still Unforgettable continues the swinging, jazz influenced sound she began on Unforgettable. By now, she has forged enough of an identity that singing “virtually” with her father, as she does on his 1952 hit “Walkin’ My Baby Back Home,” seems superfluous. Otherwise she delivers consistently on winning renditions of classic tunes like “The Best is Yet to Come,” “Here’s that Rainy Day” and “Something’s Gotta Give.” After the set was released Cole took a hiatus from performing for health issues, suggesting the album was recorded under some duress. As solid as it is the most interesting performances are actually on the “Deluxe Edition” featuring the delightful Latin-flavored tune “Summer Sun” which has an effervescent vocal bathed in percolating strings, and a wryly funny big band version of “Busted.” Cole won her ninth Grammy for the set, her second in the Traditional Pop category. Her victory reinforces her stature as a one of the best interpretive singers in contemporary popular music. In 2013 her interpretive interests extended to an album of Spanish language pop on Natalie Cole En Español.

Cole’s ability to flow between eras is impressive by virtue of her range and a deft understanding of how to balance the essence of a song with her own musical identity. Cole’s journey through her family’s musical heritage has helped her gain greater access to her artistry.

The only thing missing from her discography is a single recording that captures her gospel inspired R&B and pre-rock swing/pop personae fully in concert with each other.

“Blue Jazz,” my shorthand for the blues and R&B-soaked swing that singers like Dinah Washington, Joe Williams, Dakota Staton and Lorez Alexandria perfected, fell out of vogue at some point in mainstream vocal jazz. Many singers in this vein persisted in this style, including Ernestine Anderson, Etta Jones, and Ernie Andrews. Newer generations of jazz singers more commonly drift toward Betty Carter’s improvisational style, Peggy Lee’s hushed sensuality or arid folk-jazz than blues. Among the current generation Natalie Cole has the pedigree and experience to record some brilliant blue jazz suites.

Cole summons up all kinds of soul, humor and musicianship on the Ray Charles associated waltz “Busted” recorded on Still Unforgettable with a big band. From her ad-libs (“I’m broke y’all!”) to the tone of her voice between crooning and soul shouting she sounds full-bodied and totally in her element. Though it’s easy to cite Aretha Franklin’s most popular music as influencing Cole, Franklin’s early efforts to build a jazz career were never realized as fully as Cole’s success in this area.

As is well known, Franklin struggled to apply her powerful style to standard material at Columbia. In listening to albums like Laughing on the Outside (1963) Franklin’s power and technique sounds impressive, but she sometimes fights the songs. Pedestrian string arrangements do not help these matters. Comparatively the much looser Yeah!!! a “live” set recorded with the Ray Bryant Trio, crackles. It is easily her best work at Columbia and her most convincing jazz statement. Her other successful jazz foray is Soul ’69 a big band swing jazz album recorded at Atlantic Records that showcased Franklin’s finely honed chops in a brass-laden setting. Though her talents exceed the confines of the R&B tag she was such an iconic soul singer that this album never got its commercial due; no hit single. 1973’s Hey Now Hey was her last attempt at a jazz-oriented album. Though she does an impressive “Moody’s Mood” and soars on “Somewhere” the set is too muddled and laden with stylistically ambiguous material to gel. Cole’s success with big band swing, orchestral ballads and vocalese, combined with her R&B roots indicate that she has the tools to record the kind of blue jazz recordings Franklin long abandoned for more conventional R&B fare.

In many ways she could look to Franklin’s direct idol Dinah Washington. It’s important to remember that Washington is also a clear presence for Cole. She recorded “What a Difference a Day Made” on Stardust and “Ask a Woman Who Knows” on the album of the same title. Like Washington she knows how to inflect a lyric with a blue tone and Washington’s crisp enunciation, sultry tone, strong melodic sensibility, and laidback phrasing are all present in Cole’s recordings to various degrees. No one will ever match Washington’s tartness, but she is a good place to start for understanding Cole’s potential. Lorez Alexandria is another potential inspiration. She, more than Washington, has the combination of a gamine, silken tonality and blues grit similar to Cole’s versatile sound. I would love to hear Cole singsongs in the blue jazz canon like “Ain’t Got Nothing But the Blues,” “Please Send Me Someone to Love,” “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” “Muddy Water,” and “Save Your Love for Me” among others. These tunes would symbolize the bridge between her classic predecessors and her contemporary interpretive style. I also suspect that such recordings would complete the portrait of her career fusing her strengths and cementing her unique contributions in an era where two key outgrowths of the blues tradition, jazz and R&B have been severed.

COPYRIGHT © 2016 VINCENT L. STEPHENS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.