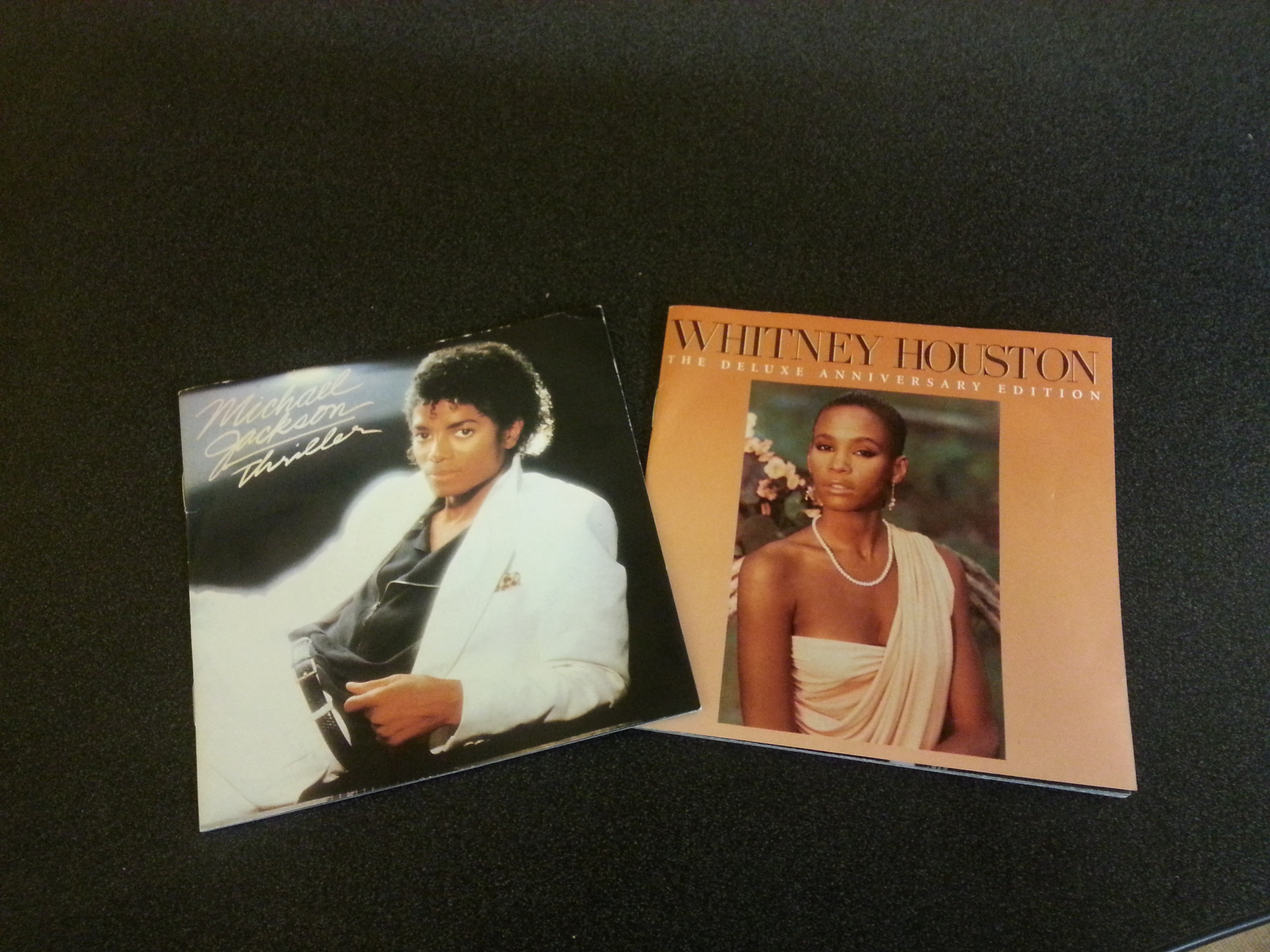

Getting Away…Letting Go…Gone: Reflecting on Michael Jackson and Whitney Houston

Though Michael Jackson passed way in 2009 and Whitney Houston in 2012 their record companies continue to market their catalogs. In 2014 Epic released Xscape, a compilation of previously recorded but unreleased material. It spawned the hit “Love never felt so good” and lot of controversy from members of the Jackson Family. After releasing a Houston compilation in 2012 Sony/BMG released Whitney Live: Her Greatest Performances in 2014. They continue to intrigue audiences in death as in life.

Thriller cover Copyright ©1982, 2001 MJJ Productions/Epic. Whitney Houston cover Copyright© 1985, 2010, RCA/JIVE label group.

Whitney Houston and Michael Jackson share reputations and roles as the most iconic black singers of the 1980s. As such they epitomized the longstanding black “crossover” dream better than any other black singers of the rock era. Or rather, as we learned from their tragic premature deaths they embodied the nightmarish side of the dream to the extreme.

Even compared to commercial heavyweights like Stevie Wonder or Diana Ross, who achieved immense success as pop-soul artists, Houston and Jackson gave up more. In the ‘70s Wonder and Ross still had to make it with black audiences first before crossing over. But Jackson and Houston reached a point much earlier in their careers where they started with the general/white/pop audience and did not need to “crossover.” They had already arrived. White audiences, and global audiences, embraced them as eagerly as blacks—maybe more so.

In morphing from black acts with presumed “specialized” urban appeal/ethnic resonance (and other industry euphemisms) they mutated into distant commodified versions of themselves. Jackson was a prodigy who became a promising, awkward teenager who grew into a handsome independent young man before becoming a human commodity with Thriller. The fragile tenderness on Off the Wall’s ballads (i.e. “She’s Out of My Life”), the recurring escape themes on its dance cuts (“Burn this Disco Out”), especially the title track gave him away, in retrospect. The leap from his sappy middle-of-the road (MOR) solo albums at Motown to Off the Wall’s layered expressions hinted at reservoirs of suppressed emotion within Jackson.

As ear candy these songs are expert pop craft. As tell-tale signs of something impending in his psyche and career they are frighteningly prescient. Thriller is almost exclusively an opportunity for Jackson to escape into meaningless accessibility tinged with paranoia (“Billie Jean,” “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’”). Content is not so much the message as feeling; like the milk you drink to cool hot foods Thriller was a rich, sweet, creamy balm that could never cool the sting of Jackson’s life in the long-term. Its beginning was his (the real MJ) end as opposed to “His” (MJ global superstar/King of Pop). The kinds of social, psychological, and emotional developments young men usually traverse from childhood to young adulthood were already complicated (stifled?) when he went into making Off, and Thriller cemented their stagnation.

Because the American popular culture industry was not built for or by blacks, black artists always struggle to get in. Once “in” they know what they have left behind (safety, comfort, empathy, cultural understanding from the black “niche” audience), they are often daunted by what they want to see (fame, success, acceptance), and what could be seen by cautious eyes (second-guessing, rejection, contempt). Fame has not proven itself as an antidote to racial pandering as figures as disparate as boxer Jack Johnson, athlete/actor O.J. Simpson, former Ms. America Vanessa Williams, and golfer Tiger Woods experienced at different phases of their careers.

Though Houston lacked Jackson’s adolescent commercial pedigree she was a young woman when Arista record exec and producer Clive Davis shepherded her into pop heaven. Even her mother Cissy’s experience as a renowned background singer and minor R&B star could not prepare her for the platform she reached with her immense vocal talents. Davis’s “hit” single mentality was broad enough for her to crossover but too narrow to really “get” who Whitney was and what she might face. This is where Farah Jasmine Griffin’s classic book If You Can’t Be Free, Be a Mystery is crucial. Her book localizes the sources of Billie Holiday’s pain and elusiveness. There’s something we cannot know (hence Mystery) because there was something Holiday was trying to protect (not hide). Drugs helped her establish this distance; the same was tragically true of Houston in many respects.

Beneath the studio gloss, the elegant phrasing, and the entertaining if often prosaic songs lies something raw and unarticulated that usually gets condensed into a broader emotional field of pop feeling. Yet this is unsatisfying because Houston was not easy to reach or understand despite her apparent commercial accessibility. Beyond the hits was someone unseen; one who betrayed the obvious sentiments of her attractive but unchallenging music. Who knows how she would have developed differently if her fame came when she was more seasoned? This is where 1990’s mediocre album I’m Your Baby Tonight is crucial. In wanting to make Houston seem “blacker” (via hiring New Jack producers like Babyface, L.A. Reid and Daryl Simmons) her record company essentially rejected who she was to win the black audience’s favor. As such she descended publicly into a black urban tale fit for Maury Povich: Erratic behavior, a loutish husband, self-destructive behavior, drug abuse, and unidentified angst. What she wanted—acceptance? understanding? fame? catharsis?—killed her. Drug use is never passive, but the gradual erosion of self occurs at slower speeds and lower frequencies.

************************************************************************************************************************************

My first thought with both of these singers is always to wonder when their biological families and black audience “families” had to let them go, hence the essay’s title. Our families, however flawed, usually know us best because they are intimate witnesses of our becoming. Jackson’s proximity to his parents and his siblings is both a testament to family support (usually rare for artists) and an understandable motivation for him to become more independent artistically and personally. Since he remained affiliated with The Jacksons (musical group) into the early ‘80s it’s not clear when his family’s respect for his solo pursuits drifted toward concern. And if his audience thought he was growing increasingly strange in the mid-80s during the acme of Thriller his family surely noticed.

Similarly, the symbolic grounding the black audience offered performers grew increasingly strained as the black managers, mom and pop record stores, chitlin’ circuit venues, and black radio formats that created the black music sub-industry, and fostered affinities between performers and their audiences crumbled under the weight of change. Music critic Nelson George’s 1989 book The Death of Rhythm & Blues chronicles this especially well. Record company consolidation, MTV etc. all widened the gaps. While Jackson has understandably attained loyalists from multiple cultures black culture is still his root. It was not until the early 1990s when he was accused of child molestation that black audiences reasserted their support for him. And this was reignited in the early 2000s when he accused record exec Tommy Mottola and Sony Music of racism prior to the launch of 2001’s Invincible.

Between Thriller and his death there were multiple lulls in the black audience’s interest in Jackson the musician. By the rise of New Jack and hip-hop in the late ‘80s he was catching up with the black audience’s taste rather than leading it. The child star that emerged as icon incarnate for black kids around the world grew into a distant relative black people cared for but had lost touch with.

Houston’s mother Cissy wisely waited until Houston reached a certain level of maturity to let her record for Arista Records, and years of “wood shedding” occurred under Davis’s tutelage. Her commercial success and stable image marked her as a responsible and competent person publicly. No one would have suspected she needed her family to intervene too much after her first two blockbuster albums in 1985 and 1987. Davis guided her career closely for years but in the early ‘90s, around the time she married Bobby Brown, Davis’s grip started slipping. The once unreachable star suddenly appeared more vulnerable (i.e. weird behavior, missed gigs) but in the most clichéd of ways. Rumors about drug use, her troubled marriage, and diva-like behavior overshadowed her music. The once unstoppable force was grounded by tawdry scandal. By the 2000s all of her recorded output began to be viewed (or rather labeled) as “comebacks” rather than records. Her personal life overshadowed her music and black audiences ate up the drama but not necessarily the music. They reveled in the tabloid shenanigans but still wanted her to be OK. A woman once viewed suspiciously as a pop princess whose “blackness” was under question was reunited with her root audience in her darkest hour. But the gaps grew so wide that by the end it’s not clear if anyone knew what to do with her or how to handle her struggles.

Labeling talented, affluent vocalists with agency as tragic “victims” is a misnomer. Houston and Jackson made choices that benefited them creatively and enabled them to amass huge fortunes. Beyond this material reality their deaths compel reflection because they always seemed to be reaching for something we’ll never quite know and slipped in the process. My guess is that their most dedicated listeners and fans will continue guessing what happened in that gap between their initial public life and their sudden deaths.

COPYRIGHT © 2015 VINCENT L. STEPHENS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.